Five years and more since the successive collapse of the pillars of the American financial system ushered in our present dire ‘unorthodoxy’, it should be obvious that overabundant money is no substitute for a lack of genuine capital. It should also be readily admitted that artificially low interest rates cannot be guaranteed to overcome the many disincentives to entrepreneurship which currently exist. How else could it be in a world where the profit motive is so universally condemned? How else when any businessman worth his salt knows that he is being asked to spend his energies and pledge his future well-being in pursuit of customers who either themselves are not financially sound or who suffer under a government whose own straitened condition may, at any moment, seek to rob them of whatever wealth they have so far managed to preserve.

In such an environment, where the ‘rentiers’ are again being slowly suffocated (in a process far too painful and protracted ever to be dubbed ‘euthanasia’), the effusions of the central banks are, all too predictably, giving rise to the most elevated of Cantillon effects in which those who have access to the cheap credit which their policy openly aims to make available can leverage it up into spectacular gains by speculating in the traditional vehicles of financial claims, real estate, and such fripperies as art and antiques. Thus, the financial wheeler-dealers flourish while the salarymen struggle onward, the retired rein in their aspirations, and the smaller business suffer in a world of uncleared markets, elevated costs, and state-subsidized and bank-evergreened zombie competitors.

Now it may be that Professor Krugman can insist that the grossly inequitable distributional effects which this brings about – letting the GINI out of the bottle as we have elsewhere categorised it – are somehow benign (his irrational hatred of the thrifty clearly overlapping with his bien pensant contempt for the rich with whom he presumably identifies them and thus overcoming his equally demagogic distaste for bankers). But we are far more sympathetic to the analysis presented by that eminently more reputable economist, Axel Leijonhufvud, who, in an address to Cordoba University in Argentina a few months back, dealt decisively with just this malign side-effect of the central banks’ ‘every tool is a hammer’ approach to policy, declaring that:-

Most of all, reliance on monetary policy has the inestimable advantage that its distributive consequences are so little understood by the public at large. But relying exclusively on monetary policy has some unpalatable consequences. It tends to recreate large rewards to the bankers that were instrumental in erecting the unstable structure that eventually crashed. It also runs some risks. It means after all doubling down on the policy that brought you into severe trouble to begin with.

Prof. Leijonhufvud, noting that the privileges extended to our limited liability money-creators are ‘in effect transfers from taxpayers as well as from the mostly aged savers who cannot find alternate safe placements for their funds in retirement’ and talked of the effortless enrichment to be had by those who can borrow at near zero rates from the central bank and leverage it up multiple times to buy higher-yielding government paper, all the while patting themselves on the back – and padding themselves in the pocket – for their genius.

Coincidentally, while writing this, we were sent a report condemning the large French banks’ lack of progress in restoring their finances to anything resembling a structure which could endure the slightest adverse gust were all these implicit and explicit state guarantees not so readily extended to them. Taking a quick look – more at random than out of any more studied approach to finding the worst offender – we checked the broad-brush financials for one of them, Credit Agricole, on the Bloomberg.

Mon vieux Agricole disposes of assets of around €1.8 trillion – not far short of a year’s worth of French GDP – against which it holds in reserve an official ‘Tier 1 Risk-Based Capital Ratio’ of 10% and a ‘Total Risk-Based Capital Ratio’ of what looks likely a highly conservative 15.4%. But therein lies the rub – namely, in the weasel words ‘Risk-Based’ and ‘Tier 1’. If we look at a good, old-fashioned measure like, say, tangible common equity to total assets, the cushion between continued existence and business failure falls to the exiguous level of 1.27%.

Putting that another way, for every euro of equity to hand, this one bank has piled €78.74 of assets – funding a hefty portion of them, no doubt with the BdF’s favourite little, officially-endorsed, ECB collateral-eligible, exceedingly short-dated titres de créances négociables. Our good Swedish professor would be in danger of choking on his smorgasbord if he were to read of such a crass degree of state-sponsored hyperextension.

We would also gently remind the reader here that, in Hayek’s sophisticated reading of the economic problems we create for ourselves, he relied heavily on a similar concept of distributional unevenness – rather than that of an indiscriminate aggregate demand shortfall – for an explanation of why the Gutenberg School of Economic Quackery should never be allowed the final word.

So, no, Prof. Krugman, savers cannot presume to be ‘guaranteed’ a positive real return on the sums they set aside (though you no doubt hope that those looking after your own, no doubt substantial nest egg will manage to achieve this very feat). But what they can rightly demand from a just society is that the only risks they run are everyday commercial ones and they are not systematically robbed by feckless politicians following the kind of crude leftist trumpery which you and your kind never cease to espouse.

No treatment of these issues would be complete without a brief nod to the spreading predilection for invoking an explanation for the inconvenient fact that we are not responding in textbook fashion to the potions, poultices, and bleedings being administered to us by our leeches at the central banks. This is the hackneyed old idea that we have somehow lapsed into a period of ‘secular stagnation’ – a wasting disease wherein our utter satiety with all the riches which a technologically mature society can shower upon us leaves us enfeebled and enervated, all compounded by the fact that our ineffable ennui has led us to procreate with ever decreasing regularity to the point it is threatening, horror of horrors, to make our blue sapphire of a planet a little less crowded than once we feared it might become.

Heaven forbid, but the latest sermoniser to propagate this nonsense was none other than Larry Summers – the man some thought might actually be a bit, well, less open-handed had anyone had the temerity to risk installing him as Blackhawk Ben Bernanke’s successor – suggesting that maybe Madame Yellen was not the worst choice, after all.

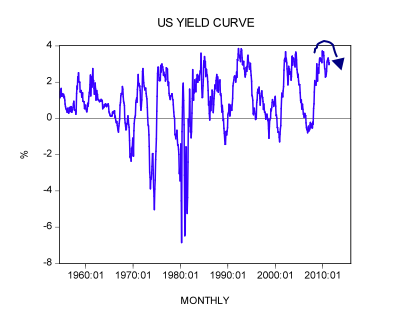

Dear old Larry has come over all Zero Bound constipated, fretting that the natural, real rate of interest has somehow become fixed down there at negative 2%-3% where conventional policy (if you can still remember of what that used to consist) cannot get at it – unless we blow serial bubbles, that is, these episodes in mass folly and gross wastefulness now being raised to the level of such perverse desiderata of which Krugman’s only partly-facetious call for a war on Mars forms an infamous example.

In fact, this entire notion is another piece of nonsense to spring from the one of Keynes’ least cogent ramblings, the notoriously insupportable notion of ’Liquidity Preference’ – a logical patch fixed over the lacunae in his reasoning when, having insisted that saving must always equal investment, all he could think of to determine the rate of interest was our collective desire to hold money for its own sake. From such intellectually bastard seed soon sprang, fully-armed like Minerva from the head of our economic Jove, the even worse confusion of the ‘Liquidity Trap.’

Not only Austrians, not only Robertsonians, not only Wicksellians like our man Axel Leijonhufvud have shown this to be a nonsense – easy enough since all of these generally look in some way at the balance being struck between the funds made available for loan according to potential savers’ subjective degree of time preference and the eagerness with which these funds are sought with regard to would-be entrepreneurs’ estimations of the profitability of their projects. But even Keynes himself all but confessed he had the whole thing backwards less than a year after that infernal tract, ‘The General Theory’, was first published.

Responding then to concerted criticism of his peculiar concept of interest rate determination as an internal mental conflict conducted in the heads of ‘framing’-prone, stick-in-the-mud, ‘college bursar’ bond-buyers who would, he felt, resolutely reject unusually low market rates on gilts in favour of accumulating cash hoards , he was forced to admit that the main part of that demand for money which he found to be the root of all macroeconomic evil was not at all related to people’s supposedly irrational desire to hoard it for its own sake, but rather was due to their wholly unobjectionable aim of ensuring a ready supply of funds prior to making planned outlays from them, something Keynes, with uncharacteristic humility, admitted in print that he ‘should not have previously overlooked’.

Since Summers himself made reference to a man dubbed the ‘American Keynes’ – that avid New Dealer Alvin Hansen – who raised this spectre, seventy years ago, let us also refer the reader to the complete dismissal of this strain of thought accomplished by George Terborgh in his contemporary 1945 work, ‘The Bogey of Economic Maturity’.

As Terborgh summarised in what he called a ‘thumbnail sketch’ of this theory:-

Formerly youthful, vigorous, and expansive… the American economy has become mature. The frontier is gone. Population growth is tapering off. Our technology, ever increasing in complexity, gives less and less room for revolutionary inventions comparable in impact to the railroad, electric power, or the automobile

Robert Gordon and Tyler Cowen are hardly the trailblazers they like to imagine they are, either, it appears –

The weakening of these dynamic factors leaves the economy with a dearth of opportunity for private investment… Meanwhile… savings accumulate inexorably… and pile up as idle funds for which there is not outlet in physical capital, their accumulation setting in motion a downward spiral of income and production… the mature economy thus precipitates chronic over-saving and ushers in an era of secular stagnation and recurring crises from which there is no escape except through the intervention of government.

x

In short, the private economy has become a cripple and can survive only by reliance on the crutches of government support.

Two hundred-odd closely-argued and empirically-rich pages later, Terborgh sums up as follows:-

If… we suffer from a chronic insufficiency of consumption and investment combined, it will not be… because investment opportunity in a physical and technological sense is persistently inadequate to absorb our unconsumed income; but rather because of political and economic policies that discourage investment justified, under more favourable policies, by these physical factors.

Hear! Hear!

As Wikipedia laconically notes in its biographical sketch of Terborgh’s protagonist, Hansen, the verdict of history was unrelenting:-

The thesis was highly controversial, as critics… attacked Hansen as a pessimist and defeatist. Hansen replied that secular stagnation was just another name for Keynes’s underemployment equilibrium. However, the sustained economic growth beginning in 1940 undercut Hansen’s predictions and his stagnation model was forgotten.

So, why should we not forget it, too? Only because, as Terborgh was only too aware, the popularity of such views is a gilt-edged invitation for continued, large-scale interventionism by the Bernankes, Summers, and Yellens of this world and there will surely come a point where the slow drip, drip of these will utterly undercut the foundation of our modern order and usher in to office a much darker series of opportunistic overlords and aspiring saviours.

On that somewhat sombre note, we will leave matters for now, with only a pair of questions to ask of our present leaders by way of an epilogue:-

If, as you and your ilk mostly do, you affect to fear that we are somehow exhausting the planet’s capacity to give our species a domicile, how can you also be worried that we may be slowing down, dying out, and using less and hence presumably be making less of a call upon Holy Mother Gaia—and doing so, moreover, in a wholly voluntary fashion?

Furthermore, if you really do believe that we are on the verge of such a ‘stagnation’ as you describe—with all it implies for the potential dwindling of income streams and the drying up of future returns on capital—how can you reconcile the current, extraordinary buoyancy in the stock market with your firm insistence that no part of the policies you have been implementing can in any way have contributed to what must therefore be an untoward degree of optimism (aka a ‘bubble’) in the valuation of its components?

Answers, please, on a postcard.

Yes savers – especially small savers, are being wiped out (ruined).

And the very rich (those who get the money from the Central Banks first) are prospering.

And all in the name of “Social Justice” and “helping the poor”.

The dishonesty of the system is sickening.

So, we’ve come to the point five years after shoulder-shrugging among central bank hanger-on economists, that it’s time to add a truly spicy variation on their monotone theme of ‘more of the same’.

What is herein described as the plight of the bankers against the reality of non-creditworthiness in the overall commercial economy, is picked up the Summers-Krugman circle as a more modern secular stagnation, one little varied from the factors laid out in Fisher’s Debt-deflation Theory of Great Depressions.

Given the reality that there is limited but hammers in the monetary policy toolbox of the classicals, it is no surprise that they discover the mechanism that is freezing financial liquidity as an inability to restore workable mechanics to the risk-reward equation that must somehow function in the capitalist economy.

We know that Summers is pretty good with arithmetic, and it would be obvious to anyone doing the math that we cannot move forward from here as there are too many debt-service payments due, and not enough new money being made to service them. It’s that Fisher thing again.

Casting our economic fate to the winds of bubble-induced, reverse-logic money management, we end up with the call of the day. I guess that when you’re traditionalist and things become bad in unprecedented ways, it gives license to call for even more unprecedented WAG solutions.

Pity their failure to recognize the cause, that being the creation of all money as debt, in the face of the laws of both simple and compound interest over a one hundred year period. There, the apparent solution would be to issue money without issuing debt and the immediate removal of associated interest burden on the economy.

For consideration, I suggest a read of Positive Money’s Modernizing Money as one alternative to bubble-icious de-stagnation. A similar debt-free money approach is taken by Adair Turner in “Money, Debt and Mephistopholes” here:

http://www.group30.org/images/PDF/ReportPDFs/OP%2087.pdf

And my personal take on why they get an “F” .

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IvDkvN0xMrs

Thanks.

Or this from

Hi Joe,

I support Positive Money, but there is a weakness in their claim that money created as debt is a big problem. I set out my reasons here:

http://ralphanomics.blogspot.co.uk/2013/03/the-money-as-debt-fallacy.html

Basically I argue that where a bank customer simply wants money for day to day purchases (i.e. a “float”) the bank will not charge interest, though it WILL CHARGE for administration costs.

As distinct from that, where anyone wants a LONG TERM LOAN, then a bank WILL CHARGE interest. Indeed where private sector entities by-pass banks and lend direct to each other, interest is normally charged.

In other words one advantage of central bank created money (or “debt free money” as PM calls it) is not the interest point. The real point is that the administration costs of central bank money are lower than in the case of commercial bank created money.

Whence Sean Corrigan’s assumption in his opening sentences that interest rates are “artificially low”?

Given the astronomic amounts that governments borrow, and given that government is a non-free market phenomenon, it’s quite possible that interest rates have been artificially ELEVATED ever since governments first started borrowing big time (about two hundred years ago).

Certainly government borrowing to fund current expenditure (as opposed to capital spending) is not justified. So to that extent, the effect of government will be to artificially raise interest rates. But even the conventional idea that government is justified in borrowing to fund capital spending (the so called “golden rule”) has been challenged in the literature.

This is a complicated question to which I don’t have the answer (yet!).

Dear Ralph, it almost sounds as if you subscribe to the ‘Crowding Out’ theory of government and ignore that they and their bankers have long since privileged the issue of their liabilities in cahoots with their partners in crime, the bankers.

Moreover, my main contention is with this ludicrous idea that the hypothetical ”real’ rate of interest – not the observable, nominal one, mind you – is somehow now negative. Even you, as a latter-day monetary Theosophist must surely accept that Mortal Man aches for satisfaction in the here and now and so must be recompensed for pushing the fulfilment of his desires out into the uncertain future.

If you do accept this, you must agree that REAL interest rates cannot be negative, not until the Four Horsemen ride out, at least.

Interest rates on what?

Money?

Warehouse receipts?

Warehouse receipt currency at fractional reserve?

Fiat currency at fractional reserve?

Asset-less debt backed currency at fractional reserve?

So many different things are at loan, there is no possible way of knowing what the interest rate should be, only the results can be seen at a given rate. Greenspan admitted they had no way of seeing what would happen. Every tinkering leads to a new round of head scratching.

When it falls down, everyone guilty has a home overseas, and those who do not will take positions in the new regime. New rulers always want people who can be trusted to do the wrong thing. Look at the former Soviet Republics.

This is what happens, without exception, when the State is allowed to be involved with money and definitions.

John,

Good question. Certainly a currency issuer should not pay interest simply for holding currency. And in fact no one gets interest for holding £20 notes. Plus, normally there is no interest paid to banks on the reserves they hold. And quite right.

Next, there’s the interest charged for a near risk free loan: e.g. a mortgage where the house owner has a 50% equity stake. I think that’s really the benchmark, and what people mean (or should mean) by the word interest.

As to riskier loans, obviously higher rates will be charged: anything up to 5,000% in the case of pay day lenders. Though a fair proportion of that 5,000% will be in respect of administration costs rather than risk.

Even if lending is from real savings (i.e. the sacrifice of consumption – thrift, not credit expansion) there is no such thing as “the interest rate”.

How long is the loan for?

Who is the loan to?

Interest rates (the price for borrowing someone’s savings) are as complicated as any other prices.

For example there is no such thing as “the price of iron”.

How much iron?

Delivered to where?

And so on.

Actually there is “the interest rate” in a general discussion of interest rates, it’s LIBOR. And if someone mentions the price of iron the minds run to the Chicago Merc price, whatever it may be, knowing of course it all depends…

My point of course is with no agreement on what money is (and take as a constant FWIW LIBOR), just what is that upon which interest is being charged? One reason for the failure of hyperinflation to appear in spite of all the “printing”, as Mish seems to be unique among pundits in noting, asset-less backed fiat currency doesn’t do much if it just sits there on the putative balance sheets of corporations as assets.

Ahhh! ‘Cash on corporate balance sheets’!

But what is much of this ‘cash’ invested in? The debt of that same government whose deficit spending gave rise to the extra revenues from whence derived the excess ‘cash’? The borrowing of customers who are going into debt in order to make their purchases from the cash stockpilers? Or into corporate debt either taken out to buy back equity – and so both to flatter the EPS figure and, worse, to make prodigious executive reward appear a non-cash item via options exercise – or, indeed, to enable a second corporate to build up its own, precautionary ‘cash pile’?

Even if masked by passing through ranks of intermediates (the Fed, commercial banks, mutual funds, hedge funds, etc), the first two are vendor financing decisions as surely as is the choice to allow an increase in accounts receivable; the third is an accounting obfuscation with no perceptible import for the creation and distribution of real resources; the last is simply a vast round-robin.