Austrian insights from the lecture hall—on DSGE models, fractional-reserve banking, and the quiet architecture of boom and bust

During my master’s programme at the University of Leeds, I engaged in a module titled Capitalism in Practice, which often unfolded as a Marxist critique of economic systems—an orientation some lecturers candidly acknowledged. In one exchange, I posed a simple but pointed question: does Marxism offer a coherent monetary theory capable of explaining financialisation and business cycles?

The answer was illuminating, not for its content, but for its absence. One lecturer conceded that no clear Marxist framework addressed the institutional mechanisms behind credit cycles or the structural fragilities of modern monetary systems. To her, as to many, financialisation appeared as an inevitable byproduct of capitalism’s evolution—an abstract drift toward finance-dominated economies. Mainstream economics, when confronted with its crises—1980s, 1990s, 2008—labels them “market failures.”

I challenged that view. Drawing from Austrian theory, I argued that financialisation is not a market pathology, but a state-engineered phenomenon. It is constructed through central banking, legal tender laws, and credit creation untethered from real savings. Ludwig von Mises warned that without true market prices, rational economic calculation collapses. Jesús Huerta de Soto goes further, calling statism an “intellectual error.” In this light, central banks—guided by DSGE models and operating under fractional-reserve banking—conjure phantom capital by treating demand deposits as both money and credit. The result: distorted intertemporal coordination and the inflation of artificial boom-bust cycles.

I presented this to her. For a moment, she paused—silent, not out of concession, but reflection. That pause, I think, spoke volumes.

Dynamic Stochastic General Equilibrium (DSGE) models

Distortions in modern economies are systematised through central bank intervention, often under the guise of scientific rigour. Dynamic Stochastic General Equilibrium (DSGE) models—favoured by institutions such as the Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank—offer the illusion of control. But in privileging mathematical symmetry, they abstract away from reality: time heterogeneity, radical uncertainty, and institutional complexity are sacrificed for tractable equations.

This critique is often caricatured as Austrian disdain for mathematics. Not so. The objection lies not in the use of models, but in their political function—as instruments of technocratic authority that mask uncertainty with pseudoscientific precision. When models are used to justify sweeping interventions “for the public good”, the line between governance and manipulation begins to blur.

The models failed dramatically in 2008. Alan Greenspan confessed to a “flaw in the model.” Queen Elizabeth famously asked, “Why did no one see it coming?” Austrian economists such as Friedrich Hayek and Jesús Huerta de Soto argue that the problem is not mere forecasting error but a deeper epistemological flaw. Markets are not mechanical systems. Prices, interest rates, and entrepreneurial expectations cannot be engineered from above. The more policymakers try, the more they distort the very signals on which coordination depends.

Fractional Reserve, Phantom Stability

Which brings us to a particularly contentious point in Austrian economics: fractional-reserve banking. Often praised for its ability to expand credit and stimulate growth, it does precisely that—though not without consequence. Critics, especially those in the Austrian camp who advocate for 100% reserve banking, argue that it undermines monetary integrity and economic stability. Far from being a spontaneous market innovation, the system operates under state sanction, propped up by legal tender laws and government-backed deposit guarantees that allow banks to lend funds they do not actually hold.

Jesús Huerta de Soto and other Austrian scholars highlight a core contradiction: banks serve simultaneously as custodians and lenders of the same deposits. This dual function, they argue, is legally incoherent and economically reckless. Huerta de Soto, in typically vivid fashion, compares the practice to placing the fox in charge of the henhouse. (He has, on occasion, offered less polite metaphors.)

The core problem lies in distorted incentives. By artificially depressing interest rates and expanding credit beyond the limits of real savings, fractional-reserve banking corrupts the price signals entrepreneurs depend on. Capital appears abundant when it is not. Investments are made under false pretences. When reality eventually asserts itself, misallocated resources must be unwound, triggering the familiar cycle of boom and bust. Worse still, these credit booms create phantom capital: investments not backed by actual deferred consumption.

Consumers spend as if the future is secure; entrepreneurs invest as if savings exist. Both are wrong. As capital goods prices lag and consumer prices surge, inflation rears its head and asset bubbles inflate. When they burst—as they did in 1929, in 2008, and as they likely will again—it is clear that what began as liquidity enhancement ends in systemic fragility.

To mainstream economists, it’s modern finance. To Austrians, it’s a state-sanctioned confidence trick—credit conjured from thin air, secured only by legal privilege and public trust.

Cantillon Effect

Enter the Cantillon Effect. Newly created money does not disperse evenly—it distorts. Banks, asset managers and politically connected firms receive it first, spending before prices adjust. Wage-earners and consumers, by contrast, get their share after inflation has done its work. The result? Asset bubbles for the few, eroded real wages for the many. Redistribution, but of a distinctly regressive kind.

This dynamic was most visible in the post-2008 era of Quantitative Easing (QE). Investor and philanthropist Stanley Druckenmiller called it “the largest wealth transfer from the middle class to the rich ever”. Asset prices soared. So too did inequality—ironically, under the watch of policymakers who claimed to be fighting it. Beneath the froth, fragility deepened. And when the boom began to wobble, central banks stepped in again—not to reform the system, but to reboot it.

The 2008 housing crash was a textbook case of moral hazard. As Christian Allred of Investopedia notes, government-sponsored entities like Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac fuelled the bubble by backing risky loans tied to inflated property values. When the bust came, it was taxpayers—not financiers—who bore the cost.

Wealth, too, trickled down—but not in the way its defenders claimed. As Mark Thornton of the Mises Institute puts it, those closest to the monetary spigot benefit first. By the time new money reaches households, its value has already been eroded.

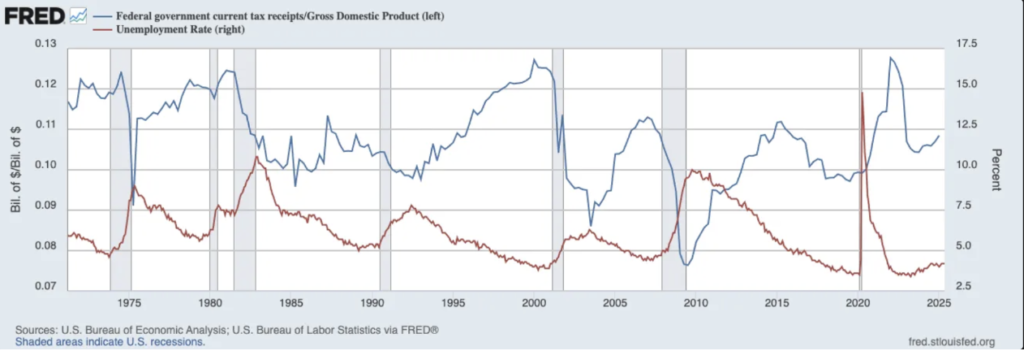

Figure 1: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1x3a9

Since the 1970s, the Federal Reserve’s addiction to cheap credit has delivered familiar—if fleeting—returns: lower unemployment, rising fiscal revenues, and buoyant consumer sectors. But the gains are superficial. Each cycle follows the same choreography—monetary loosening, artificial expansion, inevitable crash, and rescue via yet more intervention. The result is not stability but a revolving door of policy déjà vu, where structural imbalances deepen with every turn.

The data tell the tale. UK retail sales volumes doubled between 1989 and 2021, according to the Office for National Statistics—not thanks to productivity, but to credit-fuelled consumption. Asset inflation warped household expectations; real purchasing power barely budged.

Huerta de Soto’s version of the Ricardo Effect is instructive. Artificially low interest rates encourage capital-intensive production by misrepresenting savings. This temporarily boosts output, wages, and employment. But as resources shift to consumer goods in the later stages of the cycle, inflation rises and real wages fall. Investment collapses. Reality bites.

The Austrian solution? Full-reserve banking. Credit would once again be anchored in real savings. Banks would act as true intermediaries, not money creators. Interest rates would reflect intertemporal preferences—not central bank modelling. Entrepreneurial calculation, long distorted by artificially cheap credit, could realign with genuine market signals. From this perspective, financialisation is not capitalism unshackled—it is capitalism repurposed as a tool of monetary interventionism. The problem is not too little control, but too much. And the cost is not borne by policymakers or financial elites, but by those farthest from the printing press—the very people politicians claim to champion, the most vulnerable.

I couldn’t cover every nuance in class debates, but I framed this analysis in my essay for the “Capitalism in Practice” module—and was awarded a distinction. Whether read by a Marxist, a German Ordoliberal, or a supporter of the so-called “third way,” I hope it offered at least one thing: a radically different lens on financialisation—one rooted not in state engineering, but in the logic of Austrian economics.

Elias Moises Sánchez Flores is a political economist and Master’s student in Global Political Economy at the University of Leeds. His research centres on Austrian Economics, monetary institutions, and the structural roots of inflation and neo-extractivism in Latin America. He writes critically on state intervention, fiscal imbalances, and the limits of rentier-led development, drawing on the theoretical foundations of Mises, Hayek, and Huerta de Soto.