“He smiled and shook his head. ‘I can’t pay it. It is too much.’”

“Critics are men who sit and watch a battle from a high place and come down to shoot the survivors.”

- Ernest Hemingway.

The line is from Juvenal’s Satires. It translates as: Who will watch the watchmen ?

Who indeed ?

We live in a heavily regulated culture. The practice of asset management – which should be a cottage industry, given that people ordinarily buy from people, but which for most fund houses has now become a mass market, impersonalised factory process – is as regulated as any business sector. We have lost count of the number of threshold competency exams we have had to sit over the last 30 years in order to retain our discretionary management permissions from the regulator.

But some perspective is required. If we have a “bad day at work”, a client loses money, and we possibly end up losing the client. (We naturally try and avoid both outcomes, as far as practicable given the inherent nature of the financial markets, and especially given the extent to which the prices of financial assets have become hopelessly distorted by the forces of quantitative easing and central bank policy generally.)

But if a doctor, for example, has a “bad day at work”, a patient dies. Consider this extract from Henry Marsh’s excellent account of his experiences as a brain surgeon in Do No Harm:

“I am looking directly into the centre of the brain, a secret and mysterious area where all the most vital functions that keep us conscious and alive are to be found. Above me, like the great arches of a cathedral roof, are the deep veins of the brain – the Internal Cerebral Veins and beyond them the basal veins of Rosenthal and then in the midline the Great Vein of Galen, dark blue and glittering in the light of the microscope. This is anatomy that inspires awe in neurosurgeons. These veins carry huge volumes of venous blood away from the brain. Injury to them will result in the patient’s death. In front of me is the granular red tumour and beneath it the tectal plate of the brainstem, where damage can produce permanent coma. On either side are the posterior cerebral arteries which supply the parts of the brain responsible for vision. Ahead, beyond the tumour, like a door opening into a distant white-walled corridor once the tumour has been removed, is the third ventricle.”

We found this book immensely difficult to read. Those of a sensitive disposition may find it difficult, too. Marsh is ruthlessly candid. An accidental slip of the scalpel and the patient dies. A different type of slip, an inadvertent hiccup, perhaps, or an involuntary shudder, and the patient enters a coma. Another, and they are made blind forever. It’s not an easy read. But it certainly helps in providing a wider perspective on the risks, challenges and rewards of life.

According to The Guardian, by way of another grim example, renovation works at Grenfell Tower were inspected on 16 separate occasions by Kensington and Chelsea Council between 2014 and 2016, but it seems that nobody on any of those occasions spotted that the building was being covered in flammable cladding. As the first funeral of one of the victims of the disaster was taking place, Theresa May apologised in Parliament for what she described as “a failure of the state, local and national, to help people when they needed it most”.

There is only a point in regulation if it achieves something of benefit, either to the regulated, or to the customer that is the third edge of this triangle. Unfortunately, in most cases, given the nature of bureaucracy and its interaction with human nature, process entirely replaces outcome. To a man with a hammer, everything looks like a nail. To a compliance department, everything that looks like a risk needs to be stamped out. Unfortunately, the fund management industry doesn’t even have a uniform definition of risk. And to be fair, it’s quite likely that most individual clients each have a subtly different definition of the word, too.

The Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) is the main UK regulator for the financial services industry. (Its sister organisation, the Prudential Regulation Authority, is responsible for the oversight of banks and insurers.) The FCA states that it has three objectives:

- Protecting consumers

- Enhancing the integrity of the UK financial system

- Promoting effective competition in the interests of consumers.

The integrity of the City is a somewhat subjective quality, but nobody employed there should need to be instructed in the difference between ethical and unethical behaviour. And whether the market for financial services companies works efficiently should be down to the market itself to decide. Our interest in the FCA’s role is primarily focused on this first task: consumer protection. And as discretionary managers of other people’s assets, we read that more specifically as “avoiding unnecessary risks”.

First, though, we invite you to peruse the FCA’s regulatory handbook. We would merely cite another Latin phrase: summum ius, summa iniuria – the more laws, the less justice.

Try as hard as we could, we could find no specific definition of investment “risk” on the FCA website, but we think it would be fair to say that the industry itself tends to define risk, effectively, as the volatility of an investment or investment portfolio as demonstrated by its annualised standard deviation of return.

The essay that has probably been more influential than any other on modern portfolio theory is by Harry Markowitz, who in 1952 (Portfolio Selection – The Journal of Finance, 7 (1)) stated that a diversified portfolio must always be preferable to an undiversified one. This was based on the presumption that “variance of return is an undesirable thing”, and a mathematical proof that variance of return can be reduced within an equity portfolio (for example) by holding a number of different shares. Markowitz did not explicitly state that risk and volatility (variance) are the same thing. But as a result of the article, volatility and risk became synonymous and in the words of Peter L Bernstein, author of Against the Gods – which is a history of risk – “Markowitz had put a number on investment risk.”

Our friend Guy Fraser-Sampson points out that

“..despite this striking failure to offer any justification of his concept of volatility as risk, it appears to have been instantly accepted. A search against titles including the phrase ‘the nature of investment risk’ in a leading academic database [Business Source Complete] for the period from 1952 onwards yields not a single result.”

This may be the most stunning deficiency in the entire investment industry. We all know what investment risk really constitutes. Imagine being a senior director at Lehman Brothers, for example, in the summer of 2008. Your entire pension fund is invested in Lehman stock. Your entire income derives from being an employee of the company. Your entire net worth derives from the business. On 15 September 2008 you lose everything. All of your life savings are gone, and you no longer have a job, or even a pension. Now that is risk.

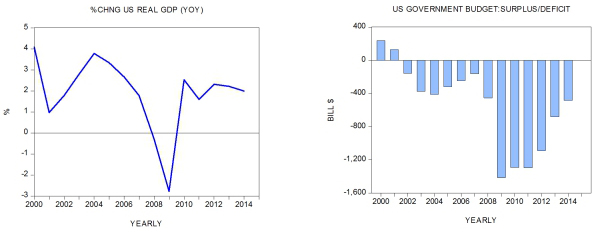

In conventional financial wisdom, there is a hierarchy of risk. Cash is deemed to be essentially riskless. (This is clearly wrong, but let’s continue.) Next up the risk ladder, for a British investor, is UK government debt. They’re called “gilts” (ie, gilt-edged investments) for a reason. Then we get to the racy stuff, like listed stocks.

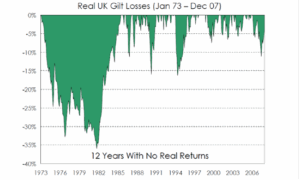

Pension funds are obligated by law and regulation to match their future liabilities with government bonds. Most financial advisers will tend to treat government bonds, or bond funds, as essentially low-risk investments. But this is investment policy out of the rear-view mirror. Just because bonds have been decent investments to hold in the past says literally nothing about their prospects in the future. But we know there have been disastrous periods, in the comparatively recent past, for bond holders.

The chart below, courtesy of Frontier Capital Management LLP, shows the real (ie, after-inflation) losses incurred by gilt investors during the stagflationary 1970s.

Anyone who bought gilts in 1973 lost a third of their money in this “low risk” asset class. More to the point, they had to wait until 1985 before they broke even.

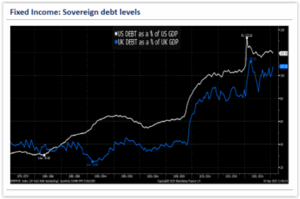

But gilts are far riskier now than they were in the 1970s. The chart below, courtesy of Bloomberg, shows the debt to GDP ratio of the UK (and US) dating back 50 years. When the UK sought an emergency loan (of “just” $3.9 billion) from the IMF in 1976, its debt to GDP ratio stood at roughly 40%. Today it is significantly more than twice that.

And if inflation, or fiat currency depreciation, really does get out of control, a portfolio of bonds runs the risk of being atomised altogether.

In his sobering analysis of the Weimar hyperinflation, When Money Dies, Adam Fergusson tells of how a young Ernest Hemingway and his wife found themselves in Germany at the time. They had the good fortune to hold French francs, which they exchanged into rapidly depreciating German marks:

“Our first purchase was from a fruit stand … We picked out five very good looking apples and gave the old woman a 50-mark note. She gave us back 38 marks in change.

“A very nice looking, white bearded old gentleman saw us buy the apples and raised his hat.

‘Pardon me, sir, he said, rather timidly, in German, ‘how much were the apples?’

“I counted the change and told him 12 marks.

“He smiled and shook his head. ‘I can’t pay it. It is too much.’

“He went up the street walking very much as white bearded old gentlemen of the old regime walk in all countries, but he had looked very longingly at the apples. I wish I had offered him some. Twelve marks, on that day, amounted to a little under 2 cents. The old man, whose life savings were probably, as most of the non-profiteer classes are, invested in German pre-war and war bonds, could not afford a 12 mark expenditure.”

Under normal circumstances – and ours today are clearly far from normal – bonds are pretty mediocre investments. But under the special circumstances that derive from rising inflation and also currency depreciation – both of which are entirely plausible in the case of the UK, given our unsustainable debt load – bonds have the potential to be disastrous. Don’t look at bonds’ recent returns in isolation; bear in mind the potential risks ahead.

The Church Commissioners, who manage assets on behalf of the Church of England, recently released its annual report.

Over the prior ten years, the Church Commissioners had delivered annualised returns of 8.3% (outperforming the Yale endowment, a universally respected institutional peer). How it delivered that return makes for interesting reading. As the FT columnist John Plender points out (emphasis ours),

“This performance was achieved with minimal exposure to fixed interest over the longest bond bull market since the second world war. And, of course, the commissioners are under no pressure now to invest in horribly overvalued government bonds — another notable advantage of not having to match liabilities closely..

“Today, the commissioners run a very diverse multi-asset strategy. While nearly a quarter of the portfolio is in property, the investment is spread across commercial, residential and agricultural property, together with indirect property and land held with a view to obtaining planning consent for housing. This is all managed in-house. Other asset categories include private equity, credit, multi-asset strategies and timber, which the commissioners started buying in 2010 when they felt agricultural land was becoming too expensive. They are now the largest owners of forests in the UK after the Forestry Commission, and have had a five-year average annual return on their investment of 15.4 per cent.

“The commissioners like to exploit their freedom as an endowment by taking seriously contrarian positions. The most eye-catching at present is an aversion for passive investing. Investment director Tom Joy argues that the performance of active versus passive funds is highly cyclical and that the fund management business is too obsessed with the recent past. With active managers underperforming at the highest rate on record, this is the last moment, he thinks, to be shifting from active to passive.

“The commissioners believe that much of their competitive advantage comes from a very intensive approach to management selection. Most of their managers are boutique firms, not household names. And they aim to avoid managers that have marketing departments.”

If we were in the position of heading up the UK’s financial regulatory effort, we would do two things. The first would be to wind up the regulator. The second would be to ensure that just before winding itself up, the FCA would issue one last recommendation. On all marketing materials denoting financial products, be they sophisticated derivatives from investment banks or retail fund documents for private clients, the umpteen pages of risk warning boilerplate in a tiny font that nobody ever reads would have to be replaced by just two words, in the largest font possible, and in blood red on the front page of said documentation. The risk warning would read, simply:

Caveat emptor.