How diesel subsidies left Potosí choking on its own transport system

By Elias Sánchez

Stepping out of Potosí’s new bus terminal—gateway to one of the world’s highest cities and, once, one of the richest in the Spanish Empire—I was met not with crisp mountain air but with a gritty breeze thick with diesel. Black exhaust curled from the engines of buses and trufis, their motors straining up Andean slopes at over 4,000 metres. “Over 4,000 metres,” confirmed Joaquín, a vendor of arvejas secas, as I squeezed into a trufi. Two bolivianos bought me a seat, a campaign jingle urging voters to “help develop Potosí by voting for Samuel”—a presidential candidate already eliminated in the first round of 17th August election—and a jolting ride uphill. “They always say that,” muttered the man beside me. In the rear-view mirror another trufi shadowed us, belching soot into the thin air—a convoy of combustion. Even with my nose covered, the stench clung.

The haze has a cause. In 2005 Bolivia introduced sweeping hydrocarbon subsidies, halving diesel and petrol prices. Nearly two decades on, these subsidies have metastasised into a fiscal burden. According to analyst Mauricio Medinaceli, they consumed nearly 3.9% of GDP in 2023. The World Bank estimates their annual cost has almost doubled in recent years.

The numbers behind Potosí’s smog reveal how this dependency has changed shape. Data from the Institute for National Statistics (INE) show that in 2009, public transport fleets were dominated by hulking microbuses with engines over 2,500cc (cubic centimeters). Fuel-hungry but relatively few, they have since declined by more than a third. Yet diesel use has not fallen—it has climbed.

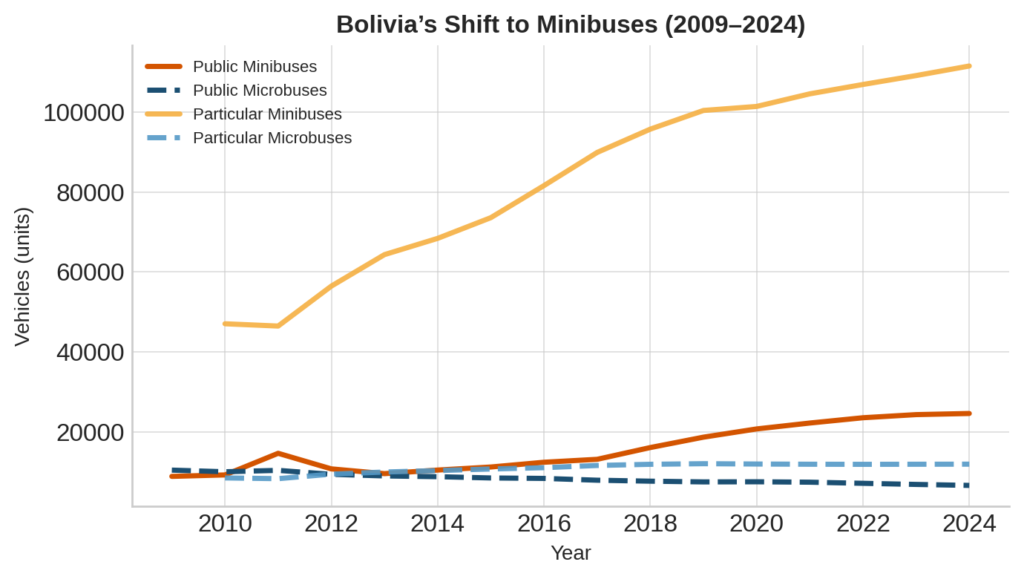

Why? Because Bolivia’s cities have traded a few big polluters for tens of thousands of smaller ones. Mid-sized minibuses—powered by 1,401–2,500cc diesel engines—have proliferated. Public-service minibuses have almost tripled, from 8,923 in 2009 to 24,642 in 2024 (See INE). Their particular-service cousins have exploded past 110,000 units. These engines may be smaller, but they are ubiquitous and run long hours through congested and steep city streets. Conservative estimates suggest this structural shift has increased aggregate diesel consumption in public transport by nearly 50% since 2009, and in the particular segment by over 100%.

The warped price signal has reshaped Potosí’s transport system. Today, most public vehicles run on subsidised diesel, chugging fumes from dawn to dusk. The fuel is cheap—but at a steep social cost. Diesel subsidies have become more than a fiscal drag; they are an environmental trap, embedding dependence on an ever-expanding fleet of mid-sized polluters.

For policymakers, the message is clear: scrapping a few old 2,500cc clunkers will not solve the problem. What’s needed is a rethink of how Bolivia’s cities move—before the thin Andean air grows thicker still.

Diesel and Petrol Subsidies

A cornerstone of economics is economic calculation. Individuals and firms rely on market prices to decide whether to buy, sell, invest, or abstain. This principle rests on marginal value theory: goods are valued according to the additional satisfaction they bring at the margin. Prices, in turn, emerge from the interplay of supply and demand for privately owned goods—including cars. When a good becomes abundant, its price tends to fall; when scarce, it rises. Prices also adjust to exogenous interventions, such as subsidies.

Markets consist of thousands of interconnected goods. Crucially, the prices of consumer goods are linked to the prices of capital goods—the machinery, raw materials, and inputs required to produce them. Without genuine price signals for capital goods, the valuation of consumer goods loses its foundation.

State intervention in capital-intensive sectors like hydrocarbons often takes the form of nationalisations and subsidies, justified as promoting “access for the majority.” Bolivia is a case in point. Since 2005, subsidies have halved the cost of diesel and petrol. The result, as the accompanying graph shows, has been a doubling of the country’s minibus fleet since 2010—a transport boom fuelled less by market demand than by artificially low running costs.

Though not among the world’s top per-capita subsidisers, Bolivia’s case illustrates how resource rents and extractivism breed structural distortions. Subsidies on diesel and petrol impose an immense fiscal burden while warping microeconomic signals. Cheap fuel encourages consumers and small-scale transport entrepreneurs to acquire vehicles they could not otherwise afford, leading to an oversized, aging, and polluting fleet.

This distortion carries heavy social costs. By disconnecting operating costs from real scarcity, subsidies incentivise overuse, clogging cities like Potosí with traffic, pollution, and inefficient investment.

In short, subsidies obscure scarcity, misallocate resources, and turn public funds into private congestion. Scrapping them is not merely a fiscal necessity but a precondition for cleaner, more efficient cities.

A Context of Dependence

Once cheap fuel becomes expected, politics stabilises around it. Subsidies buy electoral loyalty. Bolivia now imports roughly 86% of its diesel and 56% of its gasoline, depleting foreign-exchange reserves already under strain. The country’s fiscal deficit has exceeded 10% of GDP in 2023–24, and public debt has climbed to around 95% of GDP. Inflation reached 24% by the end of august this year, the highest in over a decade—further exposing macroeconomic fragility.

Attempts to reform have failed. In 2010, President Evo Morales’s effort to cut subsidies triggered the infamous “gasolinazo,” sparking mass protests and a swift reversal. Today, with inflation burning and elections looming, any attempt to dismantle subsidies risks a similar explosion. The state has trapped itself: unable to sustain the fiscal cost yet politically unable to remove it.

The Costs of Distortion

Subsidies on diesel and petrol are not merely a fiscal drain; they are a structural economic distortion. They encourage misallocation of capital—small-scale operators buying multiple vehicles they could not sustain at market prices—and worsen negative externalities: congestion, air pollution, and public-health burdens.

Bolivia’s experience shows that subsidies can create a path dependency that is as much political as economic. Breaking it will require more than fiscal tightening; it will require confronting the political economy of cheap fuel and the entrenched interests it sustains. Until then, the Andean air—and the public purse—will remain thick with diesel.

Cantillon Effects and Monetary Emission

Fuel subsidies do not only distort the signals of relative prices; they also alter the distributional effects of money creation, a phenomenon known as the Cantillon effect. First described in the 18th century by Richard Cantillon, this effect highlights that when new money enters an economy, it does not affect all actors equally or simultaneously. Those who receive the newly issued currency first—such as fuel distributors, state-owned firms, or transport operators purchasing subsidised diesel—benefit disproportionately. They can buy goods and services at pre-inflation prices. By the time the new money circulates more broadly, general price levels have risen, eroding the purchasing power of households and workers who receive it later.

In Bolivia, this mechanism is evident. To maintain artificially low fuel prices, the government covers the gap between international market prices and the domestic subsidised price. When fiscal revenues fall short, authorities resort to monetary emission—printing or injecting money through the central bank. Initially, the beneficiaries are those directly linked to fuel imports and distribution, who secure energy inputs at subsidised rates. Over time, however, the monetary expansion seeps into the wider economy, raising the prices of food, transport, and basic goods. The result is a regressive redistribution: informal transport operators may gain, but low-income households—who lack the same early access to the new money—end up worse off.

Inflation erodes dynamic efficiency, the entrepreneurial process through which resources are reallocated to their most productive uses over time. By fixing prices below their market level, subsidies freeze inefficient production patterns: entrepreneurs are discouraged from innovating, consumers adapt to artificially cheap energy, and capital is locked into obsolete technologies. Meanwhile, the money printed to sustain the system undermines purchasing power across the entire economy, fuelling further inflation, deepening shortages, and aggravating fiscal stress.

In this sense, fuel subsidies embody a paradox. They are justified politically as a tool of redistribution and social equity, yet through the Cantillon mechanism they end up redistributing regressively, entrenching inequality and inefficiency while degrading both fiscal accounts and the currency itself. What appears as a short-term relief for households thus becomes, over the medium and long term, a structural source of instability.

The Road Ahead

Driving through Potosí, the distortions of the Cantillon effect are etched into the city’s very fabric. Public officials, shielded from scarcity, cruise past fuel queues in Nissan Patrols worth over €60,000, while ordinary Bolivians wait in line beside vehicles often purchased illegally from Iquique, Chile. Subsidies, by distorting the flow of money, determine who can finance gleaming ten-storey towers and who remains in clay-brick homes beneath them. The skyline itself has become a map of misallocated wealth—a visible testament to a broken price system.

“El Cerro Rico is falling,” a passenger murmured, gesturing toward the mountain that once bankrolled an empire but now crumbles—both physically and symbolically. “Politicians do nothing.” His words frame Bolivia’s dilemma: what comes next?

Future administrations face a stark choice. One path follows the familiar script: state-led industrialisation, redistribution, and national planning. The other demands harder reforms: freeing prices, liberalising trade, and strengthening property rights in a system long derelict.

Both paths carry peril. Maintaining subsidies buys short-term political loyalty but at the cost of fiscal collapse, currency debasement, and deepening dependency. Removing them risks unrest in a society accustomed to cheap fuel as a birthright.

This is no longer just a technical debate; it is a moral one. Will Bolivia’s wealth continue to be channelled through patronage and state control—or allowed to arise from voluntary exchange and open markets?

For now, Potosí’s streets remain shrouded in diesel haze. It is more than pollution; it is the tangible symptom of a broken price system. As Cerro Rico decays, so too does the illusion that prosperity can be sustained by distorting scarcity. The next government must decide: cling to the mirage of cheap fuel—or embrace the reality that only free prices can clear the air.

Elias Moises Sánchez Flores is a political economist and Master’s student in Global Political Economy at the University of Leeds. His research centres on Austrian Economics, monetary institutions, and the structural roots of inflation and neo-extractivism in Latin America. He writes critically on state intervention, fiscal imbalances, and the limits of rentier-led development, drawing on the theoretical foundations of Mises, Hayek, and Huerta de Soto.